The Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Thailand extends its deepest condolences to the family, friends and colleagues of Lance Woodruff, a veteran club member and Vietnam War era correspondent and photographer, who recently died peacefully in Philadelphia from pancreatic cancer.

Lance was visited in his final hours at Penn Medicine by his daughter Hannah, his sister Alison, his younger half-brother Rob Werner, and Rob’s wife Mary Ann.

In his later years, Lance adopted an Old Testament beard that well suited his thoughtful and gentle – but always preoccupied – manner. He last spoke from the floor at the FCCT in May soon after his return from celebrations marking the 50th anniversary of the fall of Saigon on 28 April 1975. He had caught up there for the last time with former colleagues, a resilient band of self-described “Old Hacks” who were guests of the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Committee for the week.

“I am an historian, a writer and photographer focusing on the intersections of image, memory, imagination and 'reality,'” he once wrote. “A lifelong fascination with the Arthurian Legend and the early history of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome evolved into travel and studies of Africa and Asia, Southeast Asia, Champa, Zomia, pre- colonial Asia and Africa, independence movements, religion and society -- especially Buddhism, Christianity and Islam.”

Lance graduated from Macalester College in St Paul, Minnesota, with a double major in history and political science. A fellow alumnus in the early 1960s was the young Kofi Annan, later to become one of the most revered secretary generals of the United Nations. How closely their paths crossed is not clear, but many years later Lance wrote to the world’s top diplomat, and was delighted to receive a very warm letter in reply.

Remarkably peripatetic, Lance went on to study Southeast Asian politics at Bangkok’s Thammasat University. He was information officer for the Vietnam Christian Service, and from 1966 to 1968 served as the Vietnam correspondent for the US National Council of Churches.

That momentous period included the Tet Offensive at the end of January 1968 when the Vietnam War escalated dramatically and US diplomats suddenly discovered they were not safe even in their own embassy in Saigon.

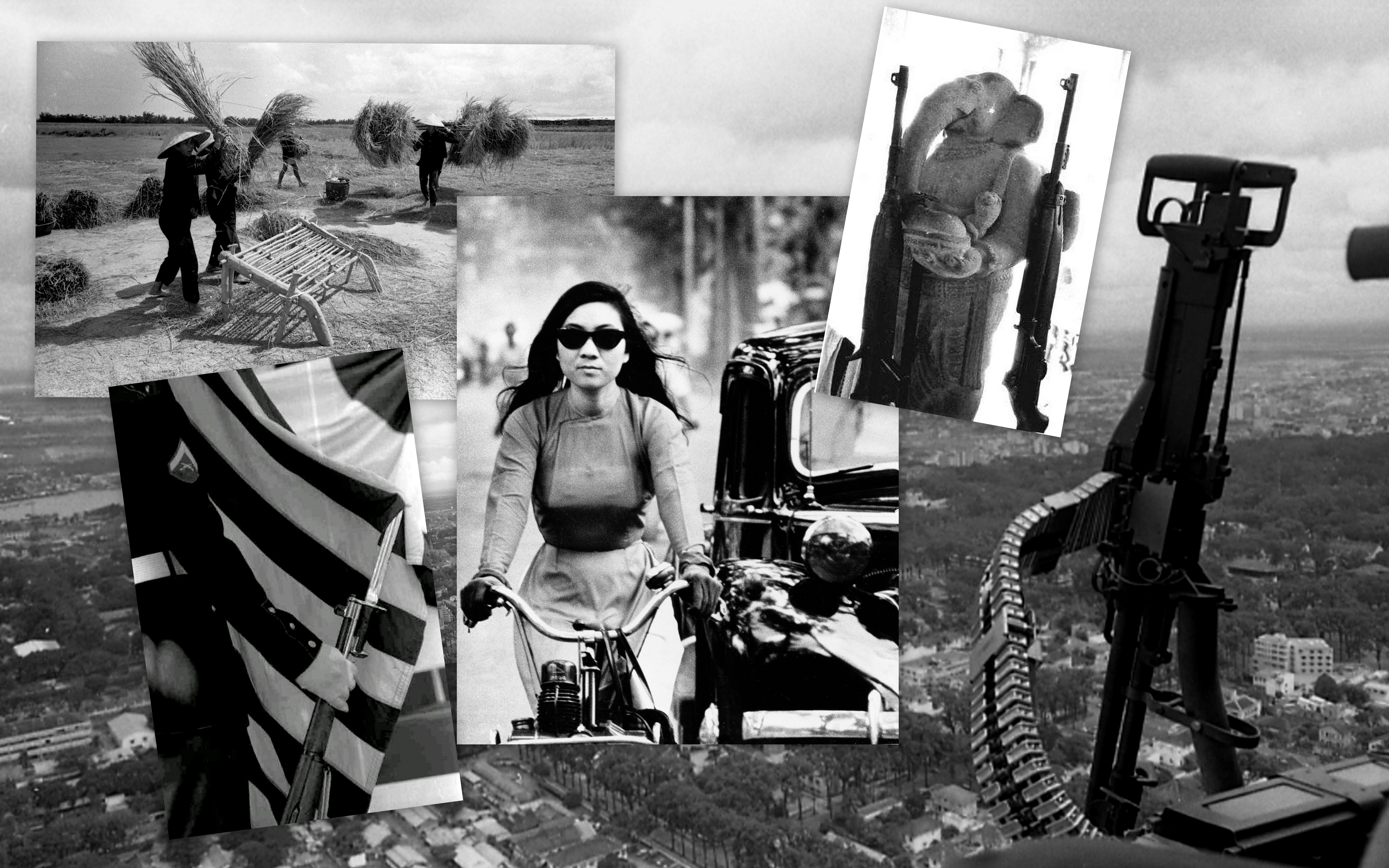

Lance covered the war, but not so much as a war correspondent. He was instead a deeply empathetic observer of how ordinary Vietnamese were affected by the terrible strife. His fine black and white photographs from that period have always been particularly admired.

Lance continued as a journeyman journalist in many places. He was at various times night editor of the Bangkok World, information officer at the Asian Institute of Technology and a photographer at The Tenderloin Times in San Francisco. He was the Mekong River Commission’s information officer after his return to Bangkok in the early 1990s.

His last full-time employment from 2005 to 2015 was as English editor at MCOT Thai News Agency, a job he undertook with immense diligence but that ended bitterly – and much to his financial disadvantage.

Lance was also dismayed when Thammasat University failed to respect his copyright regarding pictures he took of the university’s former rector, Dr Puey Ungphakorn, a brilliant economist and arguably the greatest technocrat in Thai history.

Sadly, Lance did not have the satisfaction of a compilation of his remarkable work, but very few photographers do. There were occasional small compensations, however. His unvarnished photographs of a young King Bhumibol Adulyadej dressing down a local official can be found in the opening pages of the second edition of ‘The King of Thailand in World Focus’, the FCCT’s compilation of international media coverage of the last reign published in 2007 that went on to over 40,000 copies in print.

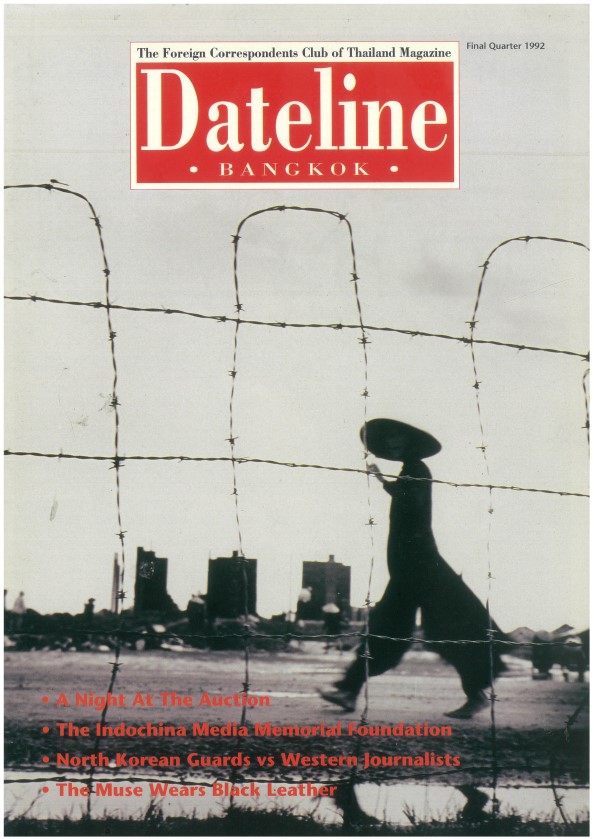

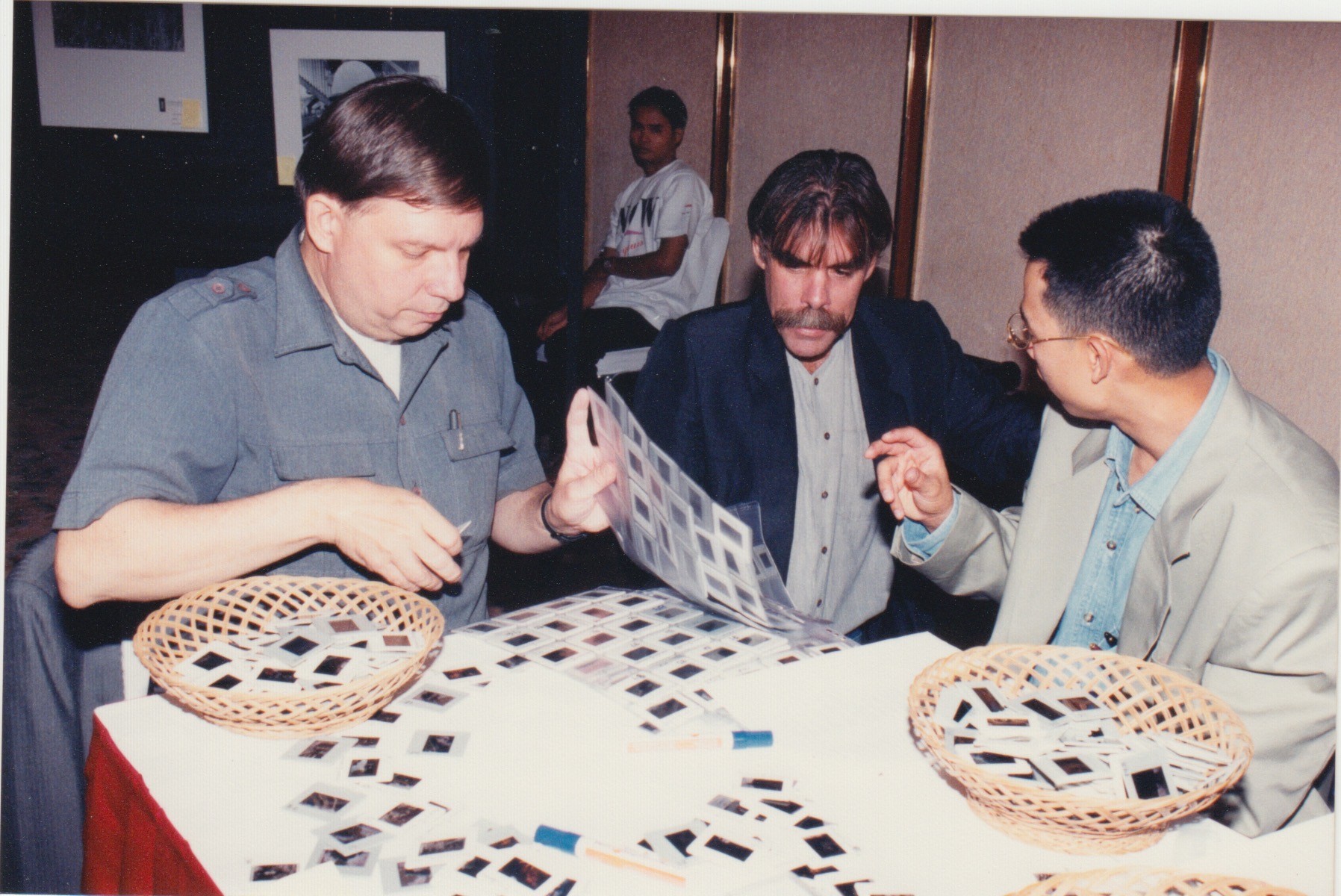

Lance also contributed some defining images to the Indochina Media Memorial Foundation. It was founded in 1992 in Bangkok by the late British photographer Tim Page in conjunction with the FCCT, and trained over 900 young journalists in mainland Southeast Asia. It also produced manuals in basic and advanced journalism in English, Burmese, Cambodian, Lao and Vietnamese.

“Vietnam and the Vietnamese were his great loves and the wonderful photographs he shot there are testimony to this love,” said, Denis Gray, a longtime Associated Press bureau chief in Bangkok, and former FCCT president and IMMF co-president.

“When the IMMF was established with Denis Gray, Dominic Faulder and Sarah McLean, Lance and I were chosen to help establish training in photography and news for journalists from Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos,” recalls Mikel Flamm, another American photographer.

That was the start of a friendship that truly endured. A few years back at a United Nations event, Lance vanished from the photography display he was supposed to be looking after. Mikel tracked him down several booths away engrossed in another exhibit.

“He reminded me of an absent-minded professor who never quite knew where he was but always wanted to see more,” said Mikel.

Funeral arrangements are still in progress but will likely take place on 20 or 21 February. It remains to be seen if Corinna Samuel, Lance’s second wife whom he married in 1998, will be able to attend from Myanmar. Lance and his first wife, Elizabeth, were married in Bangkok in 1968, and she lives in Ohio with their sons Alex and Christian.

The FCCT will arrange a wake once a suitable date can be settled. In the meantime, here is a reflection by Lance on life, death and the role of journalists in the Vietnam War published on Stefan van Drake’s ArtTraveler blogspot in early 2011:

In San Francisco in 1986, nearly 20 years after leaving Vietnam in the aftermath of the Tet Offensive, I learned and finally accepted that I was a veteran of the war.

Media coverage of Dien Bien Phu, Russian literature and the Spanish Civil War were part of my reason for going to Saigon as a 23-year-old photojournalist.

I admired Hungarian photojournalist Robert Capa who had died in northern Vietnam in May 1954. As an 11-year-old schoolboy in Ohio I listened to radio broadcasts of the siege of Dien Bien Phu in my grade six classroom and believed that civilization would essentially come to an end if 'the Viets’ were victorious over the French.

By the time I arrived in Saigon in 1966 with two Pentax Spotmatics, a 6x6 Bronica and an Uher tape recorder the size of a small suitcase filled with bricks, I imagined myself as Leo Tolstoy’s Pierre in ‘War and Peace’.

I thought that I would document war and its aftermath, walking around the edge of battlefields after the shooting was over, and that I would describe it, photograph and publish it, and then we would all stop doing these things to each other. I would write the great American novel. I imagined that war could be solved.

On a combat mission in an American A1E fighter-bomber over the Ho Chi Minh Trail west of Pleiku, however, I looked death in the face and saw nothing pretty about it.

I simply understood that I would die. Repeated dives against three anti-aircraft positions plus soldiers on the ground shooting at my aircraft filled the air with tracers. I shot back with my cameras, blindly.

On that flight I carried two items, a small leather bound King James Version of the Bible and a typed copy of ‘Monte de El Pardo’ by Spanish poet Rafael Alberti.

In Vietnam I saw death and understood something about the taking away of life and the future for women and men, for children of any age. In peacetime one prepares for a future that does not usually mean the daily approach of death.

Journalists are witnesses, [and] when one has witnessed much, there is a responsibility to share what it means, or might mean. Looking forward to the new year I survey the year past, of memories shared with journalists from many countries.

What does have meaning? What does matter? What is the value of a life?

One example comes to mind, Phung thi Le Ly, a peasant child in Quang Nam, was born a sickly two pounds — so small that her midwife wanted to kill her immediately.

"Suffocate her!" the midwife told Le Ly's mother, Tran thi Huyen. Born to a middle-aged mother at work in the rice fields when her water broke, the child wasn't expected to live.

Her mother refused to follow traditional wisdom regarding "runts”, and the infant survived, earning the nickname "Con Troi Nuoi", child nourished by God.

Today Phung thi Le Ly carries small libraries and medical services and training to the rural people of Quang Nam.

Stay Connected With FCCT

Join our mailing list or visit our events page to see what’s coming up at the club.